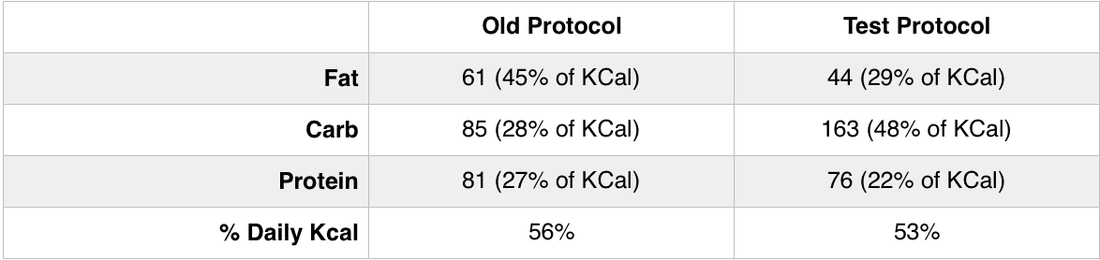

What is the problem, you ask? Nutrient timing, specifically as it relates to sleep quality. Didn’t expect me to take that direction, did you? But trust me, it’s a real thing. Let’s take a step back real quick for some context: my main goal at the moment is fat loss. I need to drop my body fat percentage enough to make bulking more effective, as discussed in Part 1 of my Diet Series. I haven’t given a ton of details about my exact diet in my video logs, but this article wouldn’t make much sense without that information. So allow me to bore you with details of what I’m putting into my body every day. Currently, I’m eating three times a day at 1 PM, 5 PM and 9 PM. I’m training six days a week for roughly 90 minutes between 6:30-8:00 PM, meaning only one of my meals comes post-training. I’m basing all of this on my current level of advancement; I consider myself an intermediate/high-intermediate level trainee. Not to continue to shamelessly plug my diet series, but this concept is also discussed in Part 1. At the moment, Sunday is my only scheduled off day. I’m imposing more of a deficit on that day in the form of a Protein Sparing Modified Fast in order to free up some more calories to allocate towards training days. I’m keeping protein stable across days to promote lean mass retention, keeping fat relatively high to encourage optimal hormone levels, and taking a more moderate approach with carbs. This is all well and good, and this rationale is surely making Menno Henselmans smile somewhere. Since apparently I’m in love with tabular representations of data, here’s what it all looks like in yet another pretty little table: These totals add up to a theoretical 20% energy deficit throughout the week. At this deficit, I should be losing 0.7% bodyweight per week. Actually, I was exceeded that rate in my first two full weeks to the tune of 2.8% and 1.1%, respectively. In athletes, there seems to be a positive correlation between speed of weight loss and loss of lean mass [1]. And there’s nothing positive about that, really. But that’s not even the issue that I’ve spotted here. We’ll save the issue I just explained for another post (although the ~300 kcal/day I’ve added back seems to have done the trick). The way I have my meals set up on training days ends up allotting the vast majority of my daily energy intake toward that last meal, post training. This makes sense, because muscle protein synthesis (MPS) can feasibly double after a training session, and building new mass is an energy-intensive process. However, I’ve been allocating macronutrients there in an indiscriminate fashion: I’m having a large proportion of fat, carbs and protein in that meal. Theoretically, this has benefits beyond what I discussed about MPS just a few lines above. Some fats, such as Omega 3s [2] and other PUFAs [3], can augment the anabolic stimulation of protein when consumed at the same time. Carbs don’t enhance this effect, but in the post training window they can help refill glycogen stores and provide energy for the process of building lean mass. This sounds like I’m just writing a post saying “look at me! Look at how smart I am and how I finessed my diet like a boss!” Which, okay, I partly am… But theres a problem here: my sleep quality hasn’t exactly been that great since I’ve taken this approach. I’ve been beginning to notice a pattern of waking up three to four separate times each night, sometimes not even needing to use the bathroom. And instead of falling right back asleep, I find myself lying in bed staring at the inside of my eye mask for at least 30 minutes (btw eye masks are regal AF and I highly recommend getting one). What’s more is that I’ve already taken steps to alleviate this. I’ve blacked out my room, limited blue light exposure leading up to my bed time, gotten more sun exposure during the day time, started supplementing with melatonin and even cut back my caffeine intake. But there’s still one stone left to turn, and that’s in the diet. The key here may lie in the nutrient composition of my pre bed meal. In 2013, Lindseth et al. found that a high-carb diet was associated with fewer wake episodes, higher sleep efficiency and a lower sleep latency (time to fall asleep) than a high-fat diet [4]. That same year, Afaghi et al. found that a low-calorie ketogenic-style diet reduced the proportion of REM sleep when compared to a control diet [5]. What’s more, the Women’s Health Initiative in 2010 revealed sleep duration was negatively associated with total fat intake [6]. These findings would all seem to implicate a high fat intake as a detriment to sleep quality and quantity, at least in comparison to a high-carb diet. This isn’t to say that we should avoid fat in the name of counting sheep; rather, it should give us reason to look into how we can shift nutrients throughout the day to keep fat high enough for hormonal benefits while still being able to get the quality sleep we need to enhance our physique. Luckily, some scientists somehow read my future mind... I mean... did some pretty cool research investigating the acute effects of the composition of a pre-bed meal and it’s impact on sleep. Once again, Afaghi et al. investigated the impact different macronutrients had on sleep, this time comparing the effect of a high-GI (glycemic index) vs low-GI meal ingested four hours before sleep [7]. Interestingly, they compared an 786 kcal meal containing either 90.4% carbohydrate in the form of Mahatma (low GI) or Jasmine (high GI) rice. I’ll save you from opening your calculator app: that’s 174 g carbs, a pretty big meal by any standard. The result? A “significant reduction in the mean sleep onset latency was observed with a high-GI compared to a low-GI meal.” What’s more, that same meal administered just one hour before bed didn’t work the same magic. The researchers hypothesized that this effect may be the result of more tryptophan entering the brain. A high-GI meal increases insulin production, which would shuttle the majority of amino acids toward other tissues (such as skeletal muscle). But tryptophan would be largely unaffected by this, resulting in a more favorable ratio between tryptophan and the remaining large neutral amino acids (LNAA). This matters because tryptophan and LNAA compete for entry into the brain. Once tryptophan crosses the blood brain barrier, it is converted to serotonin, which acts as an intermediary for melatonin synthesis. And melatonin is basically the sleep hormone. So what am I getting at here? Based on the data we have, there is reason to believe that a high-carb, high protein meal roughly four hours before sleeping will improve both sleep quality and sleep onset. But it appears that not just any high-GI carbs will do. A study of Japanese men and women in 2014 showed that among common starchy foods, only rice was significantly associated with improved sleep quality and not an equivalent amount of bread or noodles [8]. Wheat products are known to be a stress on the digestive system, which may account for this difference. All of this sounds convincing, but like I said earlier, I’m still progressing pretty well (“too well”) in the weight loss department on this protocol. Not to mention, my strength is consistently rising session to session. You know what they say, if it ain’t broke… But in the long term, consistently good sleep will ensure I’m progressing at the optimal rate vs petering out at some point. Alright, Me, you make a good case. Here’s what my old setup looked like vs the high-carb test protocol. And yes, this means another table, deal with it: The old protocol included whole milk, brussel sprouts, ground beef, white rice, cheese and a fish oil pill, whereas the test protocol includes turkey, white rice, brussel sprouts, a banana, greek yogurt and macadmia nuts. It’s important to note that in the old protocol, nearly half of my calories in that meal were coming from fat. When we speak of “high-fat” or “high-carb” meals, we’re speaking in terms of the percentages of total energy. The old protocol was a high-fat meal, the new protocol is high-carb. Here are the relevant considerations to consider when assessing this change: Nutrient Timing the Rest of the Day Notice how the test protocol has me eating slightly fewer calories inside of the Anabolic Window, the period of time post training where protein synthesis is elevated. How will I know if the 3% energy reduction is hampering my progress? By keeping tabs on my strength progression. The reason for shoving nutrients to aggressively into that period is to encourage the body properly partition those calories towards muscle building. There’s no better way to do so then by allocating calories to the time when your body is in an anabolic environment, and there’s no better way to put your body in an anabolic environment than by strength training. However, if my strength continues to progress at the same rate from session to session as it has been on the old protocol, then it would appear I have nothing to worry about. In theory, improved sleep quality would actually enhance my progress. This change also means I’ll be eating relatively fewer carbohydrates during the day and replacing it with more fat. If you read my other dietary experiment already regarding Carb Tolerance, you’ll see that I’m no stranger to a higher-fat approach throughout the morning and perform the same in the gym with a high-fat pre-training meal vs a high-carb pre-training meal. Also, keep in mind that when meals are properly sandwiching training, the nutrients from the pre workout meal will also have an impact on training performance and the subsequent recovery process. Maybe the 3% of energy I shaved off the post workout meal and added back to the pre workout meal could aid performance? Weight Loss Rate This is my main goal here, so if this test protocol somehow threw my results for a loop in this department, I’d obviously revert back to the original protocol. But since the caloric deficit will be accounted for the exact same way, I don’t see that happening. Again, theoretically, better sleep could lead to more fat loss. Sleep Quality (Obviously) This was the whole point of this article in the first place. As I mentioned, I was waking three to four times per night, having trouble falling back asleep and waking up a bit groggy under the old protocol. An easy way to keep track of this would simply be to see if those parameters improve. So What’s the Verdict? I implemented this change on December 5th. Currently, it’s December 19th, which means 14 days and 12 training sessions have occurred since the beginning and conclusion of this experiment. There was also one night of moderate drinking thrown in there for a Christmas party, and three days where I had to push my training session to earlier in the day due to my schedule. On those days, this protocol wasn’t put in place. As far as I can tell, subjectively, this change has paid some dividends in improving sleep quality, especially as it relates to the time it takes to fall asleep. That’s not to say that this was the magic cure-all for sleep, but it helps. I previously noted that with the old protocol, I’d often find myself waking up three to four times per night for no reason; that number decreased on most nights to zero to two times waking. Oddly, I noticed that these random wake times were coming closer and closer to my actual wake up time. Whereas I used to wake up in a scattered fashion (say 1:45, 3:20, 6:30), now I seemed to be sleeping through most of the night on most days only to wake up around 7:45 or 8:00. And no, I couldn’t exactly fall back asleep. But I chalk this up as a minor win, because I’d rather have a longer, solid block of sleep than a more fragmented block of sleep any day. I definitely noticed improved energy upon waking up as well that seemed to last longer during the day. Again, these are subjective measures. I don’t put too much stock in my sleep app data, because the past few days (without fail) I wake up to find it nestled underneath me in a wad of blankets, which it explicitly states “not to do.” Oops. How about the objective measures, then? You know, weight loss, strength, all that good stuff. Remember: I added roughly 300+ kcal/day back into my diet since switching protocols in order to slow down the weight loss rate I was experiencing; this can be a significant confounder. And another thing that could confound results what a minor elbow injury I experienced in the middle of the week. I spent a good chunk of gym time messing around with different exercises that wouldn't aggravate the injury instead of putting in strenuous work. This decrease in output, however slight, may have thrown my results a bit off track compared to other weeks. Lo and behold, that’s exactly what I found. Based on weekly averages, my weight still dropped by roughly half a pound in the week I employed this change, but that’s a bit short of my target weight loss. I credit this more to the addition of calories rather than the allocation of carbohydrate. Strength continued to increase, and based on my training log, I can tell no discernible difference between the protocols. However, I suspect this would change if my sleep was still compromised in the long term. All told, this change allowed me to get to sleep faster and stay asleep longer without negatively affecting performance in the gym or (drastically) hindering weight loss. I’d imagine if I were to make the change at the appropriate calorie intake, I’d get the best of all worlds: better sleep, better weight loss and better performance. Which is exactly while I’ll continue to implement this protocol for the foreseeable future. As I wrap this up, I can already hear some of you asking, “hey, isn’t this just Carb Backloading?” I suppose, in a way, it follows roughly the same principles. But the considerations taken to get there are much, much different than the dogma proposed in Carb Backloading. For those who follow CBL, carbs at night is somehow “magical” and allows you to eat cake and cookies to your hearts content, so long as you do so after the sun sets. At least that’s what the book hooks you with... uh, I mean, says. It also advocates the carbs-only-at-night approach no matter what time of day you train and no matter what level of advancement you may be at. This is fundamentally inaccurate. There is also no mention of improving sleep quality in CBL to my memory (it’s been a while since I’ve read that book, honestly). Look, anyone can blindly throw darts at a dart board and hit a bullseye on occasion. I simply don’t value blind luck as much as I do trial and error through sound principles. Call me old fashioned. I’ll admit, I was caught up in the CBL hype for a while. Insulin was the boogeyman, and as long as I kicked his ass during the day with my coconut-oiled-up coffee and gorged on Pop-Tarts every night, I was on the road to ripped. To be fair, I got in pretty damn good shape on that style of protocol. Gotta love being a teenager. I actually got down to an all-time low in body fat and stayed relatively strong. But this was also a time in my life where I had a very minimal stress load, lived on my own, and didn’t have to prep or pay for my own food (ah yes, the college life). And I’m also 100% sure that this style of eating led to some very undesirable (borderline disordered) eating patterns that I struggle with to this day. But I digress. And by digress, I mean this is likely too in-depth for further discussion and will require a separate blog post. The take home message here, kids: if you identify a potential problem with your diet, list the pros and cons, plan a sound experimental protocol, give it time to take effect, and objectively weigh the results. You know, that same scientific method stuff we pretended to learn in the seventh grade. In-Text Citations

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

DisclaimerThe techniques, strategies, and suggestions expressed in this website are intended to be used for educational and entertainment purposes only. The author is not rendering medical advice of any kind, nor is this website intended to replace medical advice, nor to diagnose, prescribe or treat any disease, condition, illness or injury. |