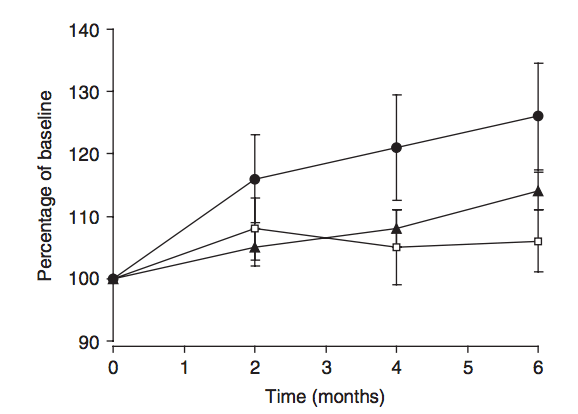

The reason that this theory doesn't stand up boils down to two things: 1) Strength is a skill, not an attribute 2) General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) doesn't have a predefined end point Here's the deal: every time you introduce a new exercise to your routine, you enter what's known as the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) cycle. It's not a sickness or anything; it's simply a cycle that dictates your body's response to a given stressor. Yes, exercise is a stressor; that's how it encourages change in your body. If you've never done an exercise before, or better yet, if you've never even stepped into a gym before, then these new exercises will impact your body much differently than someone who has experience with these exercises. Since you've never exposed your muscles to this specific stress before (and each exercise is highly specific, even front squats & back squats require different adaptations), your body will kick into high gear to try and bring things back to homeostasis after you've completed your workout. Remember: exercise is a stress. You're placing tension on muscles through resistance, which creates microscopic damage to your muscle tissue itself. Again, this is okay. This is literally the goal of strength training. I won't bore you with those details; just know that your body puts a number of things in motion that will allow you to recover from this stress & "supercompensate," meaning you'll be better able to handle the same stress in the future. This course of events follows the GAS cycle: alarm, accomodation, exhaustion. The aspect of this that everybody feels right away is muscle damage, or "DOMs" (Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness). This is the soreness your feel; the exact feeling that discourages you from walking up a flight of stairs after a heavy squat session. This feeling of soreness is always highest when the exercise is "newest" to you. As a beginner, everything is new, and your body's response mechanisms to training aren't very efficient yet. As a result, the soreness you feel is much more intense for a much longer time, often discouraging some trainees from ever returning to the gym. The good news: this doesn't last forever. Your body's ability to recover from this consistent stressor increases each time you do the exercise. This is due to the Specific Adaptation of Imposed Demands (SAID) principle. Basically: whatever you continually do, your body will become better at handling. Additionally, if you stay consistent with the same exercises for a number of weeks, you gain the skill of strength at this specific exercise. Instead of saying "that guy is strong," we need to start saying things like "he has a strong deadlift" or "she has a strong squat." These are much more accurate terms, because you gain specific strength at specific tasks, and this strength is a function of two things: your nervous system's ability to adapt, and your muscle's ability to adapt. In the beginning weeks, a hefty amount of the strength you gain comes from your nervous system simply gaining experience with the movement. This is why good form is so crucial to nail from the start. For nearly three months (!!!), the amount of strength you gain from an exercise is largely based on these neurological gainz. This is depicted in the graph to the left, adapted from a research review by Folland et al. (2007). The black circles represent strength; the white boxes represent neural adaptations, the black triangles represent muscular adaptations. As you can see, for nearly three full months (roughly twelve weeks), you're going to be adding pounds to the bar mostly because you're getting better at doing the movement itself. Your muscles will also adapt in this time period, just not to the same extent as your nervous system. All three metrics track upwards for months in a given exercise (in this case, leg extensions). At this point, you may be questioning your entire training career, because the friendly fit pro at XSport told you that you need to be changing your exercises every four weeks for maximal gainz, bro. Not only does your nervous system not fully adapt in that time period, the amount of muscular adaptations you can make lasts at least six months and increases in a nearly linear fashion. I say "at least" because it's resonable to think you can continue making size gains after this point on the graph above, we just don't have that data. But the data we do have refuting this idea of a four to six week limit is pretty convincing. You can go on Pub Med and find plenty of studies where the subjects gained size & strength all the way through a three to four month training protocol with the same exercises. Like this one (16 weeks/4 months). And this one (16 weeks/4 months). And this one (14 weeks/3.5 months). And this one (12 weeks/3 months). If all of these programs encourage strength & size gains for at least three months, what good reason do we have to change programs any time sooner? It's foolish to think that something as highly advanced as your nervous system & muscular system operates like a magazine subscription; as if there's some defined end point to how long you can progress at a given exercise. I'm not sure if this is simply a tactic to increase a client's perceived effort, or if this was a genuine misunderstanding of the GAS cycle... Either way, you confuse, you lose (sorry, I had to). By giving yourself a completely new set of exercises every four to six weeks, like most personal trainers are taught to advise, you're becoming a "perpetual beginner." You will always be sore. You will always look like a baby giraffe in the gym since you will never get fully proficient at any single exercise. You definitely won't maximize your muscle gainz, either (the horror). The common problem here is that people mistake this extra soreness for a better workout, and are easily fooled by the amount of strength they can gain on a new exercise in just a few weeks. Don't fall for this. You now know that the soreness is simply a byproduct of training that decreases with experience, not the end goal. You also know that the majority of the strength you gain in these first few weeks comes from your skill at the exercise itself, not because "you're gaining a ton of new muscle." The simple solution is to be intellegent about selecting your exercises from the jump, and utilize them as long as you're able to make progress (a.k.a. months, if not years). As with most things relating to fitness, the amount of progress you make in response to a program should be the driving force, not some arbitrary time point. The more proficient your nervous system gets at the exercise, the more weight you will be able to utilize. The more weight you utilize, the more muscle you build. The more muscle you build, the higher the amount of stress you must place on your body to encourage new adaptations. This is progressive overload in a nutshell. From this day forth, pick your exercises carefully, hone your skill of strength, and ride these exercises 'til you can't progress any further.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

DisclaimerThe techniques, strategies, and suggestions expressed in this website are intended to be used for educational and entertainment purposes only. The author is not rendering medical advice of any kind, nor is this website intended to replace medical advice, nor to diagnose, prescribe or treat any disease, condition, illness or injury. |